Anderszewski, 56, is speaking on a Zoom call from Edinburgh, where he has just given a recital at the Edinburgh International Festival. A large part of his current repertoire is the late piano works of Brahms, whose Intermezzi he performed in Edinburgh. Many of the Brahms pieces, written in 1892-93, have an introspective cast, and Anderszewski says they seem to reflect the composer’s state of mind and disappointments in life.

‘They are the last things he wrote for the piano – a kind of farewell,’ he says. ‘It’s cruel to think like this, but it’s very sad – (the pieces are) sort of the testimony of a failed life.

‘You know his motto: Frei aber einsam – free but lonely. He was someone who had recognition, who was respected, who led a comfortable life, didn’t struggle to survive, who had good friends – a fantastic composer – and yet something failed. I don’t know – this is what I feel in this music. It makes me very sad to play it.'

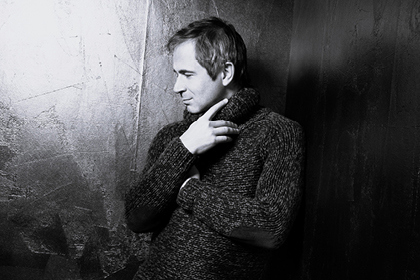

Anderszewski is making only his third tour of Australia, having first appeared with the Australian Chamber Orchestra in 2001 and then at the Australian Festival of Chamber Music in 2015. He is renowned for his supremely refined and controlled performances, but absences from the stage also have punctuated his career.

He earned a certain notoriety – perhaps more accurately, respect – at the Leeds International Piano Competition in 1990 when, unhappy with his performance, he simply walked off the stage. Within a year he was making his debut at Wigmore Hall.